Logstash CSV with Custom Geo-Enrichment

The city where I live, Washington, DC, has a public bicycle share program called Capital Bikeshare. One of the first things I did while learning Elasticsearch was to load the public system data available on the capital bikeshare program’s website. [1]

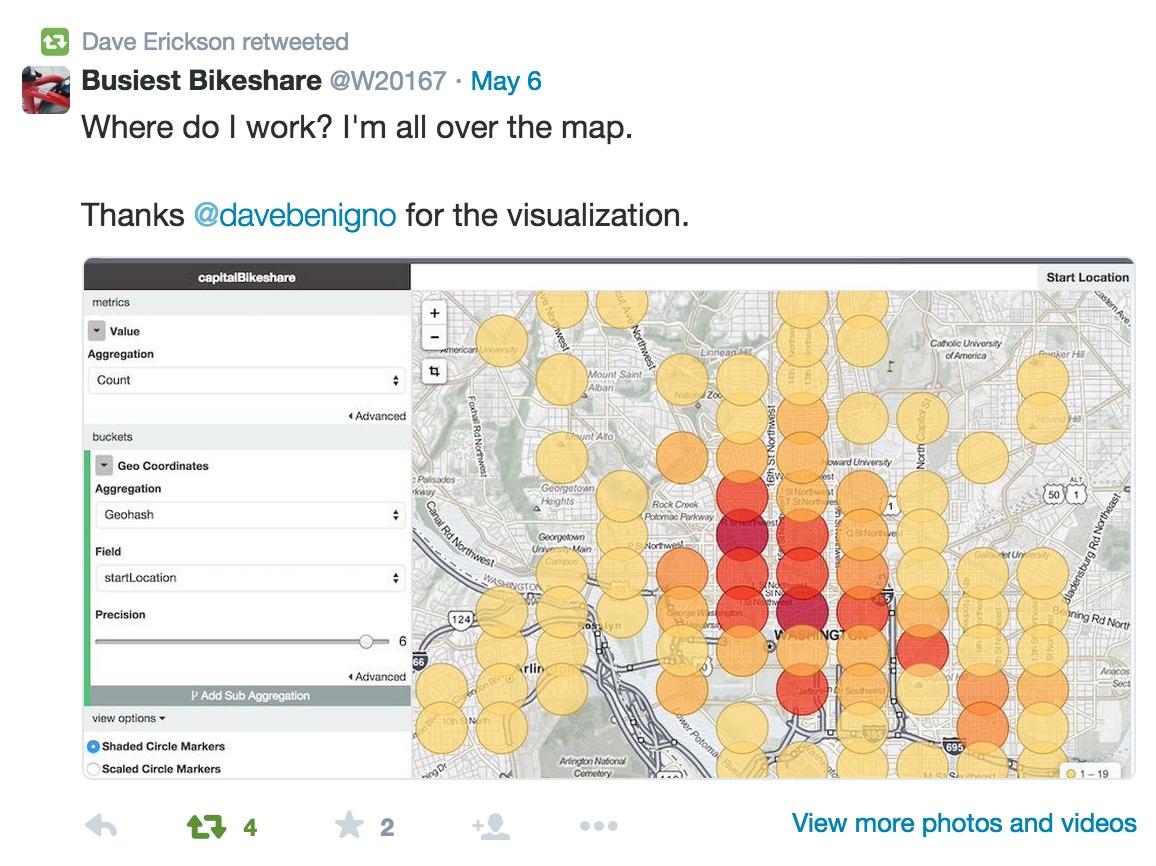

The results were fun. I got to learn the ELK stack with real data and I even got to talk with Capital Bikeshare’s hardest working bicycle on twitter:

Originally, I wrote the CSV to JSON conversion code in python. This is typically the quickest approach to extract-transform-load (ETL) jobs for me. As a dev, my scripting productivity outstrips the benefits of a more full fledged ETL library for small proof of concepts and demos. But, as I’ve described before in this blog, custom scripts tend to be too brittle and costly to maintain for a group project. So, in the spirit of eating all the tasty dogfood, I decided to revisit the CSV loading to get some more hands on experience with Logstash [2], an open source log / data processing tool from Elastic.

Below are the steps I used to process the CSV data with Logstash into Elasticsearch. Hope you find it useful!

#Step 1: Explore the Data Formats

Format 1:

Duration,Start date,End date,Start station,End station,Bike#,Member Type 14h 26min. 2sec.,12/31/2010 23:49,1/1/2011 14:15,10th & U St NW (31111),10th & U St NW (31111),W00771,Casual 0h 8min. 34sec.,12/31/2010 23:37,12/31/2010 23:46,10th & U St NW (31111),14th & R St NW (31202),W01119,Registered

Format 2:

Duration,Start date,Start Station,End date,End Station,Bike#,Subscription Type 0h 7m 54s,12/31/2013 23:58,New York Ave & 15th St NW,1/1/2014 0:06,23rd & E St NW ,W01407,Subscriber 0h 26m 23s,12/31/2013 23:56,Rosslyn Metro / Wilson Blvd & Ft Myer Dr,1/1/2014 0:23,Rosslyn Metro / Wilson Blvd & Ft Myer Dr,W00020,Casual

Format 3:

Duration,Start date,Start Station,End date,End Station,Bike#,Subscription Type 0h 5m 56s,7/1/2014 0:01,Takoma Metro,7/1/2014 0:07,Maple & Ritchie Ave,W20813,Registered 0h 18m 17s,7/1/2014 0:01,13th St & New York Ave NW,7/1/2014 0:19,Neal St & Trinidad Ave NE,W21178,Registered

Format 4:

Duration,Start date,Start Station,End date,End Station,Bike#,Subscription Type 0h 10m 35s,2014-10-01 00:00,Wisconsin Ave & O St NW,2014-10-01 00:10,17th & Corcoran St NW,W20503,Registered 0h 4m 50s,2014-10-01 00:01,Columbus Circle / Union Station,2014-10-01 00:06,4th & East Capitol St NE,W20487,Registered

I make note of some differences:

- The ‘Duration’ notation changes after format 1

- The date format isnt’ ISO 8601 standard, doesn’t have a time zone, and changes in format 4

- Station names sometimes have a station number in parenthesis at the end

- The nomenclature for a Capital Bikeshare subscriber switches between ‘Subscriber’ and ‘Registered’

#Step 2: Basic End to End

I find it’s good to start ETL jobs breadth first. By that, I mean setting up a working pipeline all the way from input to output with no initial processing and iteratively improving the parsing from there. This is where I started with Format 1. I made the following logstash configuration in a file called ‘format1.conf’ that does nothing other than use the built in CSV filer to break out the colums:

input { stdin { } }

filter {

## ----- CSV PROCESSING --------

csv {

columns => ["rawDuration","startDate","endDate","rawStartStation","rawEndStation","bikeNum","memberType"]

}

}

output {

stdout { codec => rubydebug }

}

I then pipe a small sample of one of my source files through this with a command similar to:

head -n 3 2010-Q4-Trips-History-Data.csv | sed -e "1d" | $LOGSTASH/bin/logstash -f format1.conf

The output shows a ruby debug printout of the top few lines.

#Step 3: Cleaning up Station Names

I add a filter step to remove the station numbers in parenthesis after station names. This uses the GROK filter patterns for %DATA, which matches anything and %INT which only matches numbers. I found having the list of standard grok filters [3] and regular expression language [4] open while coding to be pretty useful.

## ----- CLEAN STATION NAMES --------

# remove optinonal station number from end of the station name

grok {

match => [ "rawStartStation", "^%{DATA:startStation}(\ \(%{INT}\))?$"]

remove_field => "rawStartStation"

}

# remove optinonal station number from end of the station name

grok{

match => [ "rawEndStation", "^%{DATA:endStation}(\ \(%{INT}\))?$"]

remove_field => "rawEndStation"

}

#Step 4: Parsing Duration and Doing Some Math

Durations are stored like the following 1h 10min 5sec, so to calculate an actual number for analytics I’ll need to break apart that field and do some math. The math in Ruby doesn’t zero-initialize variables that havn’t been defined, so I’ll make sure to fill the variables with zeros first myself.

mutate {

##start values at zero

add_field => {

"durHours" => 0

"durMin" => 0

"durSec" => 0

}

}

mutate {

## add_field can only populate strings, so I'll convert to integers here

convert => {

"durHours" => "integer"

"durMin" => "integer"

"durSec" => "integer"

}

}

## ----- INTERRPET DURATION ------

grok {

match => [ "rawDuration", "(%{INT:durHours:int}h\ ?)?(%{INT:durMin:int}min\.?\ ?)?(%{INT:durSec:int}sec\.?)?"]

overwrite => ["durHours", "durMin", "durSec"]

}

## And then I'll do the math to compute the duration, in minutes of the ride

ruby {

code => " event['duration'] = (event['durHours'] * 3600 + event['durMin'] * 60 + event['durSec']) / 60.0 "

remove_field => ["rawDuration","durHours","durMin","durSec"]

}

So in this case I was able to insert custom ruby into the logstash configuration without writing a plugin. Pretty useful. I don’t know enough to guess at what point this becomes a maintenance or performance problem. Hopefully the ruby is only being interpreted / compiled once, etc. I don’t think I’d want to do anything too complex with an inlide code snippet like this anyways.

#Step 5: Convert dates to ISO 8601, set @timestamp

The Elasticsearch output step is going to depend on the output JSON doc having an event time called timestamp so that it can bucketize the indexes into timeranges. Converting time settings in Logstash turns out to be a huge time savings over messing around with date libraries in scripting languages, which I always have to relearn each time I do it.

# adjust date to ISO 8601

date {

match => ["endDate", 'MM/dd/YYYY HH:mm']

timezone => "America/New_York"

locale => en

## if you don't put a target, the new value is put in the @timestamp field

target => "endDate"

}

#Step 6: Interpreted Fields

From the first time I loaded this data in Kibana, I know it was interesting to be able to add filters for whether or not the trip was a round-trip, starting and ending at the same station, as well as having a consistent value for the member type. Let’s enrich and clean the data with some more inline ruby code:

## ------ Behavior ------

ruby {

code => " event['behavior'] = (event['startStation'] == event['endStation']) ? 'Round Trip' : 'Point to Point'"

}

#make all data sources conform to 'Subscriber' and 'Casual' for memberType

ruby {

code => " if (event['memberType'] == 'Registered') then event['memberType'] = 'Subscriber' end "

}

#Step 7: Geo Enrichment

Here’s where I got stumped for a minute. I want to add latitude and logitude coordinates to the bikeshare data so that I can look at the data on maps in Kibana. However, Logstash only comes with an IP -> Geospatial filter. In python I had loaded an XML file from Capital Bikeshare that had the station names and lat,lon pairs into an in-memory dictionary (hashmap) and just done O(1) lookups for every event to pull the geosptatial term for the start and end stations by name. To do this in Logstash it turns out I’d have to build my own custom filter plugin. Good news is that it’s super easy.

To use a custom local plugin (there is probably a cleaner way to do this with ruby gems, but I’ll learn that some other day) I add the following to my execution line: (the –pluginpath option is new)

head -n 3 2010-Q4-Trips-History-Data.csv | sed -e "1d" | $LOGSTASH/bin/logstash --pluginpath . -f format1.conf

This tells logstash to look for new filters defines inside a local ‘logstash/filters’ folder.

I then made a custom subclass of LogStash::Filters::Base that loads in a CSV file worth of location, lat, lon triples into a ruby global hashmap during the registration step, and then does the lookup and new field assignment as a filter. Source code for the filter here source [5]

Now I can add the geo enrichment filter in a simple clean step in my Logstash configuration

## ----- Process Geospatial --------

geoEnrich {

database => "/Users/dave/dev/examples/cabi/logstash-attempt/fullDCStations.csv"

source => "startStation"

target => "startLocation"

}

geoEnrich {

database => "/Users/dave/dev/examples/cabi/logstash-attempt/fullDCStations.csv"

source => "endStation"

target => "endLocation"

}

#Step 8: Adding an Elasticsearch template

So the data now looks something like this (after dropping the ‘message’ field and adding a ‘city’ field)

{

"@timestamp": "2010-12-18T14:41:00.000Z",

"host": "Astaire.home",

"startDate": "2010-12-18T14:41:00.000Z",

"endDate": "2010-12-18T14:47:00.000Z",

"bikeNum": "W00295",

"memberType": "Subscriber",

"city": "Washington, DC",

"startStation": "Potomac & Pennsylvania Ave SE",

"endStation": "Eastern Market Metro / Pennsylvania Ave & 7th St SE",

"duration": 300,

"startLocation": [

-76.9862,

38.8803

],

"endLocation": [

-76.995397,

38.884

],

"behavior": "Point to Point"

}

Much cleaner than how we started!

Because I want to load data into a set of time-range specific indexes in Elasticsearch rather than one big index, much like logstash data, I’ll need to set up an index template in Elasticsearch so that it knows how interpret fields and analyze the strings I pass it in JSON, which doesn’t convey much in the way of type of indexing instructions.

The following code, meant for execution in Sense, adds a template and alias rule. Strings are by default ‘not_analyzed’, my dates are respected, and my geospatial is treated like globe coordinates. I leave the _all field on, as I’d like to allow full text search on all the fields for now.

PUT _template/bikelog

{

"template": "bikelog-*",

"settings": {

"number_of_shards": 1,

"number_of_replicas": 0

},

"mappings": {

"_default_": {

"dynamic_templates": [

{

"string_fields": {

"mapping": {

"index": "not_analyzed",

"omit_norms": true,

"type": "string"

},

"match_mapping_type": "string",

"match": "*"

}

}

],

"_all": {

"enabled": true

},

"properties": {

"endDate": { "type": "date"},

"startDate": { "type": "date" },

"startLocation": { "type": "geo_point" },

"endLocation": { "type": "geo_point" },

"yob": { "type": "integer" },

"startStationId": { "type": "integer" },

"endStationId": { "type": "integer" }

}

}

}

}

POST /_aliases

{

"actions" : [

{ "add" : { "index" : "bikelog-*", "alias" : "capitalBikeshare" } }

]

}

#Step 9: Load the data

Next I load the data by changing the output stage:

output {

#stdout { codec => rubydebug }

stdout { codec => dots }

elasticsearch {

index => "bikelog-dc-%{+YYYY}"

index_type => rides

manage_template => false

host => localhost

protocol => http

}

}

I make an alternate .conf file that adjusts for the differences in the 4 CSV formats and build a .sh script to load all my data samples.

Here’s the full Logstash example for the first data format bikeshareFormat1.conf [6]

And that’s it! I think the Logstash conf is much more readable than my hacky python script, and it’s easier to adapt to different inputs and modular use cases where I want to reuse portions of the code and processing logic.

I hope people just starting out with logstash find this useful. There are a lot of other bikshare systems out there that publish system data in similar but not identical formats that logstash can parse. I’ll be interested to see how much of this logstash configuration can be reused.

- [1] Capital Bikeshare System Data

- [2] Logstash

- [3] Basic Grok Filters

- [4] Grok Regular Expressions

- [5] geoEnrich Filter Source

- [6] bikeshareFormat1.conf