Software Engineering lessons I learned playing The Legend of Zelda

24 years ago I was given a gem under the Christmas tree: The Legend of Zelda, (TLOZ) for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) which is without a doubt my favorite video game of all time. The game was innovative. It had a persistent memory module and non-linear map exploration, which were both very rare for console games in 1987. The game itself had a number of cool computer science techniques buried in the assembly, but that is not what I want to focus on here. I want to talk about how playing the game can inform Software Engineering.

24 years ago I was given a gem under the Christmas tree: The Legend of Zelda, (TLOZ) for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) which is without a doubt my favorite video game of all time. The game was innovative. It had a persistent memory module and non-linear map exploration, which were both very rare for console games in 1987. The game itself had a number of cool computer science techniques buried in the assembly, but that is not what I want to focus on here. I want to talk about how playing the game can inform Software Engineering.

Here are my take-aways:

1.) Learn from others

In the game:

The first time I beat TLOZ, it was on the original save-file started way back on the day I first put it in my NES. After spending literally weeks of my life spread over more than two years I thought I was pretty good; right up until I went to a friend’s house and watched him beat the game in less than 90 minutes without dying once. How did he get so good you may ask? Well, his annoying cousin had poured a 20 oz. Coke into the NES and damaged the cartridge. As a result his save feature stopped working so if he powered down the machine or even lost all his health he’d have to start over. As a result he had become very good at playing. According to TwinGalaxies.com the world record is 31 min and 37 seconds. For an idea of what this entails look up “Legend of Zelda speed run” on Youtube.

In SW engineering:

As a professional software consultant working for a vendor, I get to travel around to lots of teams and I love being humbled by some of the real hackers out there. Being ‘good’ at programming isn’t always the same thing as providing value for companies or customers, but it can’t be ignored. Finding the talent around you and learning everything you can from them is critical to keeping up your skills. Also, the second you feel comfortable with your skill level and think you are the best coder you know … watch out. It’s probably a good sign you are out of touch.

2.) Acquiring tools early pays off down the road

In the game:

Link, the protagonist, starts the game with three heart containers. Once you have reached five containers the old man over the waterfall will allow you to take the magic sword, which does about twice the damage to monsters as the starting wooden sword. Having the sword as early as possible will make the early portion of the game go much much faster.

In SW engineering:

It is easy to start writing code the first day of a project, and often managers will push for this to claim “earned value” as early as possible. However, getting organized and distributing / training the use of tool suites can be a huge productivity boost if you make the time to investment in them from the very beginning a project. The cost to your schedule will be made back as long as the tool’s productivity boost is amortized over the length of the project.

3.) Work on tasks in the order that makes sense

In the game:

In TLOZ the eight dungeons are labeled 1 through 8 and go up in difficulty accordingly. You have to collect a triforce fragment (piece of a magical artifact) from each dungeon in order to proceed into the final challenge and save princess Zelda. However based on the location of the dungeons and the locations of other things you will need to collect in the over world, there are far more efficient orders that are absolutely necessary if you want to beat the game in less than an hour.

In SW engineering:

I was taught to 1) specify requirements up front, 2) data model, 3) write queries, 4) load data, and then finally 5) test. It turns out the reverse order has big advantages and often leads to more successful projects. Writing automated tests, loading data as-is into a flexible database that doesn’t enforce schemas in order to scale / perform, and then building a proof of concept and soliciting feedback from an early demo works far better.

4.) The manual isn’t always correct

In the game:

The NES was the North American version of the slightly different Japanese Family Computer (Famicom) hardware which caused a tactics hint in the game’s manual to be lost in translation. One of the hardware differences was that the NES lacked the Famicom’s microphone, which could be used for user input in gameplay. In TLOZ there was a rabbit like monster called the Pols Voice which on the original Famicom version of the game could be killed by yelling or blowing into the microphone. The North American manual for TLOZ included a misleading hint that the monster’s weakness was “loud noise”. The only item / weapon you acquire in the game that made a loud noise is the Flute which, despite millions of North American player’s attempts, has no effect on the creature.

In SW engineering:

RTFM is a beloved IT / Tech Support acronym, but it can get you into trouble. I’ve run into plenty of documentation errors, undocumented quirks, and even preemptively documented features or API hooks that either don’t exist or don’t do anything in current release of products and systems.

5.) Use features for what they do, not how they are marketed

In the game:

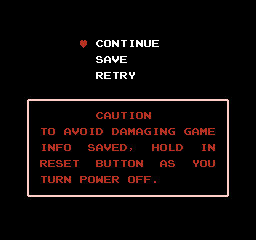

The save feature in Zelda is meant for playing the game over several sessions. Most players are only familiar with the Continue / Save / Retry screen after dying (going to down to zero hearts) in the game. However, you can exit to this screen by hitting a combination of controls on the 2nd player NES controller after hitting start on the 1st player controller. The Continue function was probably meant for continuing the current game state after dying without overwriting the current save file. However the specifics of the Continue function are the following:

- does not revert Link’s inventory to the last save file (that would be Retry)

- moves Link instantly to the current dungeon entrance or over world stating point

- set’s Link’s hearts to three

In SW engineering:

I work primarily with a product that is marketed as a Big Data / unstructured information platform. However, if you only apply what it does, not what it is sold as, it turns out that it also makes an excellent data warehouse for legacy structured information pulled out of mainframes and relational databases.

In previous jobs I would often have software languages and platforms pushed on my team by well meaning architects and customers who had researched marketing materials. I have found that technical evaluation of real features and use cases can often find hidden strengths and weaknesses specific to the problem at hand. Checking yourself is invaluable.

6.) Perfectionism and Completionist tendencies can get in the way of timely success

In the game:

If you are attempting a speed run in TLOZ, the first thing to learn is that you don’t have to kill every monster in the game or traverse every room of every dungeon. Big portions of the maze like dungeons can be skipped, and you can walk right past most enemies as long as defeating them isn’t a trigger for opening the next door and you don’t need the treasure they drop. Also if the goal is speed then taking a couple of hits shouldn’t really worry you. Just keep moving, there are no points awarded for never taking damage.

In SW engineering:

Hitting schedules and time to market advantage can be everything to a software project. Just because code can be better doen’t meet it has to be better. Keeping a close watch on perfectionist tendencies is important. Whole features that are were envisioned in early designs might be discovered to be a lower priority and never need to be built.

7.) Performance doesn’t always matter

In the game:

TLOZ has wretched performance problems when there are too many enemies on the screen or when scrolling between some over world map sections. The game loop will slow down, and when scrolling there is screen tearing, which will be familiar to modern game players who have chosen not to enable monitor VSync. While this can be nit-picked and criticized, the programmers of the game actually knew what they were doing an made difficult memory vs performance tradeoffs when delivering a very fun and stable software product that pushed the limits of the Famicom and NES hardware early in console’s life cycle, sold millions of copies, and started a successful Nintendo intellectual property which has driven customers to their products for decades.

In SW engineering:

Sub-second response time is now the expected performance metric for quality web sites. Amazon.com’s performance vs. sales conversion anecdotes are becoming engineering dogma. However, performance needs still need to be looked at on a case by case basis. Fast code may be sexy and well tuned code can run orders of magnitude faster than a merely functional implementation, but sometimes none of this really matters.

In a former life, I wrote a piece of Java to import a difficult custom legacy email archive into our project’s databases and search engines. The code could convert millions of emails in a 24 hour period. I have very clear memories of having a independent (paid by the hour) software reviewer spending hours reading code and writing up a criticism of the software’s design. We had to inform him politely that while he was quite correct in his comments regarding Java best practice, the conversion was still orders of magnitude faster than either the search engine’s indexer or the destination storage medium and that no further improvement to code would affect the success of the project. When he argued that we should still improve the software so that we wouldn’t be handing slow code to the operations and maintenance team we had to inform him that after the official run of the converter on the legacy data there would never be a need to run the code again and there would be nothing to maintain.

8.) Sometimes the hard parts take skill

In the game:

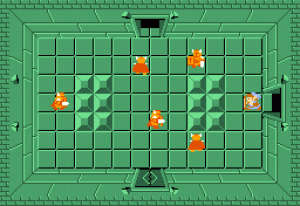

Some rooms of enemies can be skipped, but others can not. One of the toughest enemies in TLOZ that often can’t be skipped are the Darknuts. (Where do they get these names?) These shielded evil knights have to be attacked from the side or rear which is made more difficult by their agressive and unpredictable turning logic. Quickly clearing a room of Darknuts without taking damage either takes lots of bombs or true video game skill. Manual dexterity with the controller, timing, and reflexes are all required.

In SW engineering:

Sometimes all the tools, agile process, people skills, teamwork, and fancy new technology are no replacement for an actually talented and knowledgeable programmer. The ability quickly master a new language or real skill in an old language often trumps whatever buzz words and newest fads are being slung around a software project. Most of the code we write professionally is not that exciting and isn’t doing anything that complicated or difficult. However, assigning the rare complex parts of a project to a “bad programmer” (not sure how to define that better) is usually a one way ticket to disaster.

What other engineering lessons have you learned from playing your favorite games? I’d be interested to hear what you think?

— Dave